Real estate investors often wonder why a developer might choose to pay what seems to be an unusually high rate of mortgage interest when compared to prevailing rates. Well, the truth is, sometimes it’s in their long term interest to do so, instead of raising equity capital. This article explains the whys and why not’s from an insider’s perspective.

Key Points

- There are three ways to fund a real estate project: debt, equity, or a combination.

- The costs associated with the money or capital required for a project from the various sources of capital is called the “cost of capital” and is vital to determining a developer’s “optimal capital structure.” It all hinges on the concept of ROE (Return on Equity), which very much takes into account leverage.

- The choice of debt, equity, or combination financing is exceedingly complex and will depend on the circumstances and metrics of each project. At the very least, you may now have a better understanding of why sometimes a real estate developer will take on a high-interest first or second mortgage, bearing say 10% or 12% where going rates for standard mortgages or lines of credit are a lot less.

How does a developer fund a real estate project?

A developer needs capital to fund land acquisition, construction, and all soft and hard costs associated with a real estate project. In the absence of an unlimited bank account, they have three options: debt financing, equity financing, or a combination.

Debt financing is accomplished through borrowing. Usually, this: (i) means a higher ratio of investment via debt capital as opposed to equity capital; (ii) allows for tax-deductible interest (i.e., the interest paid on debt is a business expense and is deductible); and (iii) utilizes leverage to increase the return to equity owners.

Leverage is using borrowed money (debt) to amplify or increase potential returns from a project. It allows a developer to multiply buying power in the marketplace. So, for example, if the project costs $100, the developer could get 10 investors to chip in $10 each. They each own one tenth of the project. When finished, let’s presume the project will be worth 133.00. Now, each investor’s share is worth 13.30! Well the developer knows banks are in the business of lending money so the developer (and his investors!) know the bank will come in for $60 of the cost of the project! Whoo – woo! The investors only have to put in $40! So, for $40 the equity investors have $100 of brick and mortar. But once the building is finished those $40 investors will have building worth $133.00! That’s not bad. If we were to increase the amount of indebtedness by another $20, the investors would only have to put up $20! Now for $20 you get a building worth $133. That’s how leverage works! The more debt you “lever” into a project, the less equity you need; the smaller the equity requirement, the greater the return on that equity!

Equity financing refers to selling part of the project to investors who then become equity owners in the project. Equity holders generally get paid last, after any debt holders, so it is natural to expect a higher rate of return given this higher risk. Given more risk to an equity investor, the cost of equity, or in other words the return expected from an equity investment, is generally highest — except in the case where the developer is able to keep equity for itself and benefit from owning more rather than less. The only time a developer has to share ownership of a project is when the developer needs more equity.

There are three ways to fund a real estate project: debt, equity, or a combination.

Choosing between debt financing and equity financing

The “cost of capital” is generally the return expected by the suppliers of capital for their contribution of such capital. It is vital to determining a developer’s “optimal capital structure” – where you have an optimal balance from various capital sources (such as debt and equity) to reduce the overall weighted average cost of capital (more on this later). It all hinges on the concept of ROE (Return on Equity) which very much takes into account leverage. The actual calculation of ROE is “net income” of the business (i.e., income after expenses (including debt repayment!) and taxes) divided by the shareholder equity. As debt is subtracted from the calculation, the ROE increases. In fact, if the ROE appears too high, it may be a warning sign that there is too much debt in the enterprise. Generally, an ROE equal or less than 10% would be considered poor.

Typically, equity financing returns deliver a higher IRR (Internal Rate of Return) over the life of the project than debt financing which is reasonable when you think about. Debt financing is generally secured. If something goes wrong, the secured lender can step in, seize the assets and repay themselves. Equity is full “at risk”; it’s not secured. If something goes wrong, the equity investor is out of luck! They potentially lose everything. Therefore an equity investor will demand more in return than a debt investor. In real estate it is not unusual at all that an equity investor will look for a return of 20% or more on its investment. And because they are an owner, they expect that forever! If the need for additional equity could be satisfied with high interest rate debt, then that becomes a credible alternative for the developer. If high rate debt is 14%, but the developer anticipates being able to pay it all back in 3 years, debt makes a lot of sense. A developer with an eye on maximizing ultimate profit will be understandably jealous of keeping as much equity as feasible and therefore may prefer to pay a risk premium for mortgage financing.

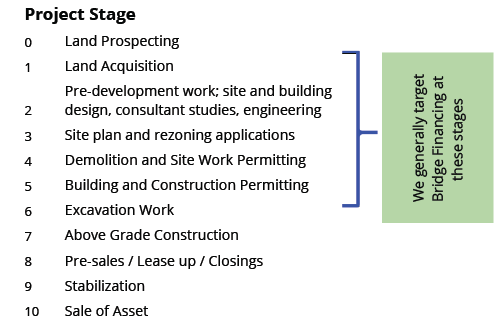

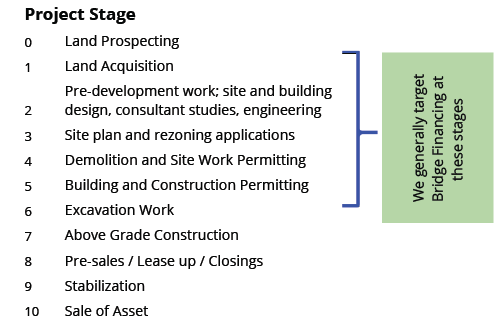

There’s also “bridge financing” (which really has nothing to do with bridges), which is a type of mortgage financing that is a premium when compared to the risk free rate of return, but a discount if you compare it to the cost of equity. It’s often used by developers to temporarily finance the cash flow for a short period of time (ergo, the “bridge”). Instead of injecting additional equity, they will need to fund the financing gap and bridge the project until it reaches the next stage of development or a subsequent financing stage. Generally, bridge loans are short term (12-36 months), pay interest only so it is non-amortizing, and have a well-defined exit strategy.

Here’s what a typical project lifestyle looks like and what kind of financing is utilized during different project development stages.

A developer may also choose a combination of debt financing and equity financing, coming up with an “optimal capital structure” that balances both and keeps in mind the cash requirements of the project at its various stages.

What are cost of debt and cost of equity?

If you need financial capital to construct an asset and then sell the asset, the interest expense for borrowing the capital is the cost of debt. Equity also has a cost, in the form of profit-sharing, and this is the cost of equity or the expected rate of return a fellow owner would expect for a similar risk profile investment. The weighted average of a project’s cost of debt and cost of equity is generally the cost of capital. The lower your overall average cost of capital, the more profit you can keep for yourself as the owner.

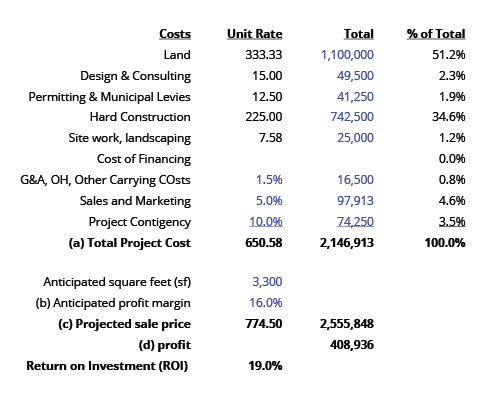

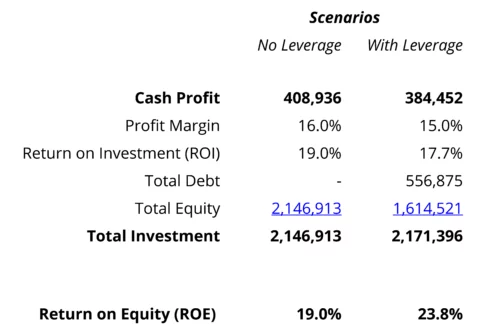

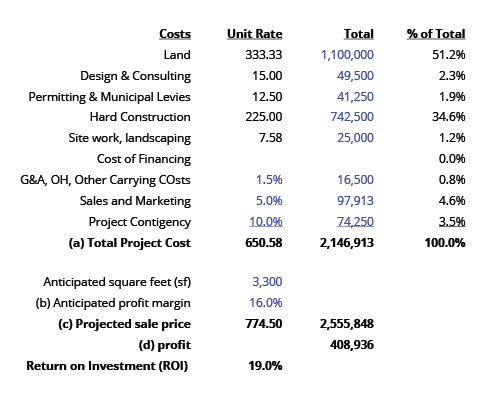

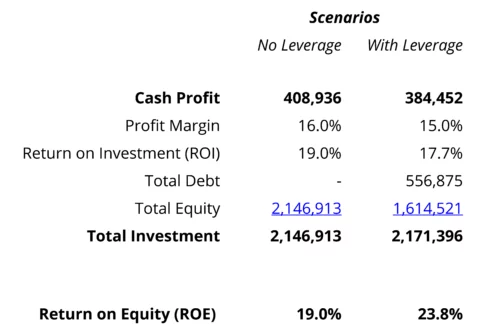

Consider a small project where the developer is planning to do a build and flip, with the below Pro-forma budget. This model below assumes a duration of 12-18 months: In the above No Leverage scenario, the developer maximizes the cash profit. However, they have to inject 2.146M of their own equity. For every dollar the developer invests, i.e. their equity injection, they will earn a 19% return or 19 cents for every dollar of equity. When a party invests for an ownership interest, then they have an equitable interest, or equity, and have a beneficial interest in the profits from the project. Put another way, an equity investor will likely expect or require a 19% return on their invested equity capital (the “expected return” or equity’s “cost of capital”).

In the above No Leverage scenario, the developer maximizes the cash profit. However, they have to inject 2.146M of their own equity. For every dollar the developer invests, i.e. their equity injection, they will earn a 19% return or 19 cents for every dollar of equity. When a party invests for an ownership interest, then they have an equitable interest, or equity, and have a beneficial interest in the profits from the project. Put another way, an equity investor will likely expect or require a 19% return on their invested equity capital (the “expected return” or equity’s “cost of capital”).

Whereas if someone were to invest and own the debt or mortgage of a property, then they become a debtholder entitled to a return defined by a predetermined interest rate. As a debtholder, you will get paid first, but that’s why your return is fixed. As an equity holder, you may get paid last, but you keep the rest of the upside.

What is leverage?

As stated above, leverage is using borrowed money (debt) to amplify or increase potential returns from a project. In some scenarios, for every dollar a developer invests, they can earn more per dollar by investing less equity. Consider this example:

By taking on additional debt and actually reducing the nominal dollar profitability, the developer achieves a few strategic objectives. It frees up over $550K of the developer’s capital, which they can deploy to another site, thereby diversifying their portfolio and helping them line up additional sites (a pipeline) for future work. It adds additional liquidity into the project. And financially, it increases the rate of return or ROE for every dollar the developer invests. Instead of earning $0.19 for every dollar invested, the equity owner earns a projected $0.238!

Borrowing from a private lender vs bringing on additional equity partners

We’re going on a math tangent now — stay with us! Even if you don’t speak equations, seeing real-life examples is a helpful way to better understand investing concepts.

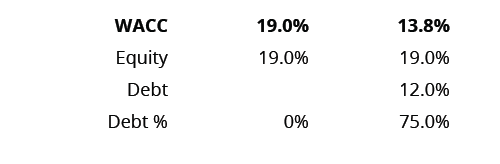

The weighted average cost of capital (WACC) is calculated by the formula:

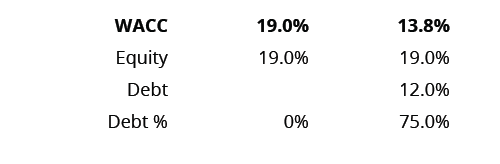

(Proportion of Equity Capital %) * (Cost of Equity) + (Proportion of Debt Capital %) * (Cost of Debt) = [100% * 19% + 0% * 12% ] = 19%

Your debt holders only demand 12%, but equity partners will want their 19% return. From a project point of view, the cost of that capital is going to be 19%! It’s the expected return your equity holders expect to receive by investing in the project. If you took on debt even at 12%, the math would work out to be 13.8%. So, overall, you can pay $0.138, or pay $0.19 for every dollar invested.

Your debt holders only demand 12%, but equity partners will want their 19% return. From a project point of view, the cost of that capital is going to be 19%! It’s the expected return your equity holders expect to receive by investing in the project. If you took on debt even at 12%, the math would work out to be 13.8%. So, overall, you can pay $0.138, or pay $0.19 for every dollar invested.

Ask yourself: Which project has a lower cost of capital? As the principal owner of the project, you want to drive down your cost of capital as much as possible. That way, you can take on projects of varying profitability and be competitive with how much you can pay for the residual value of the land at the time of acquisition.

The choice of debt financing, equity financing, or combination financing depends on the circumstances and metrics of each project.

How to get started

Funding a real estate project is a complex subject. We hope you now have a better understanding of why sometimes a real estate developer will take on a high-interest first or second mortgage when going rates for standard mortgages or lines of credit are a lot less.

Still have questions? Fundscraper is here to help its community wade through these kinds of considerations which are key to analyzing the underpinnings of its project offerings. We aim to provide our clients with the ability to make informed decisions and deliver a transparent investing process. Contact us today to learn more about your real estate investment options.

In the above No Leverage scenario, the developer maximizes the cash profit. However, they have to inject 2.146M of their own equity. For every dollar the developer invests, i.e. their equity injection, they will earn a 19% return or 19 cents for every dollar of equity. When a party invests for an ownership interest, then they have an equitable interest, or equity, and have a beneficial interest in the profits from the project. Put another way, an equity investor will likely expect or require a 19% return on their invested equity capital (the “expected return” or equity’s “cost of capital”).

In the above No Leverage scenario, the developer maximizes the cash profit. However, they have to inject 2.146M of their own equity. For every dollar the developer invests, i.e. their equity injection, they will earn a 19% return or 19 cents for every dollar of equity. When a party invests for an ownership interest, then they have an equitable interest, or equity, and have a beneficial interest in the profits from the project. Put another way, an equity investor will likely expect or require a 19% return on their invested equity capital (the “expected return” or equity’s “cost of capital”).

Your debt holders only demand 12%, but equity partners will want their 19% return. From a project point of view, the cost of that capital is going to be 19%! It’s the expected return your equity holders expect to receive by investing in the project. If you took on debt even at 12%, the math would work out to be 13.8%. So, overall, you can pay $0.138, or pay $0.19 for every dollar invested.

Your debt holders only demand 12%, but equity partners will want their 19% return. From a project point of view, the cost of that capital is going to be 19%! It’s the expected return your equity holders expect to receive by investing in the project. If you took on debt even at 12%, the math would work out to be 13.8%. So, overall, you can pay $0.138, or pay $0.19 for every dollar invested.