Experienced investors consider Alt A residential mortgages a great secured product, offering a higher return than Canada Mortgage Bonds and traditional first residential mortgages. Yet to the uninitiated, the Alt A residential mortgage market is just another real estate investment offering. We’ll explain what it’s all about.

Key Points

- The risk in the residential non-conforming mortgage market is tradeable with the risk in the conforming market. The real difference between the two is that borrowers in the non-conforming market come with stories — they are “storied mortgages.”

- Canada’s residential mortgage market can be divided into two segments: “conforming” residential mortgages and “non-conforming” residential mortgages.

- Conforming mortgages have the benefit of mortgage insurance, but most non-conforming mortgages do not qualify for insurance.

- Changes in the regulatory environment have resulted in a much stronger borrower entering the private mortgage market.

Canada’s residential mortgage market can be divided into two segments: “conforming” residential mortgages and “non-conforming” residential mortgages.

An overview of Canada’s residential mortgage markets

Canada’s residential mortgage market can be divided into two segments: “conforming” residential mortgages and “non-conforming” residential mortgages.

A conforming mortgage is either fully insured by one of the mortgage insurance companies, or which is a non-insured conventional mortgage with loan-to-value of 80% or less. Borrowers with these mortgages have strong credit histories and files that are fully documented in terms of income verification and other important aspects of the loan applications. Conforming mortgages often receive the best interest rates from mortgage lenders. Our Schedule A banks dominate the conforming mortgage market.

Conforming mortgages that have the benefit of mortgage insurance make up the backbone of what are Canada Mortgage Bonds. Our big banks don’t just sit on their mortgages. To generate further income for themselves, lenders originate mortgages, pool them, then sell the pool as mortgage backed securities (MBS) to the government. To pay for the MBS, the government sells Canada Mortgage Bonds (CMBs) to investors (think pension funds, insurance companies and the banks themselves).

If the borrower is using mortgage financing for the purchase of a recreational property or housing for a family member, or the borrower is purchasing a residence for investment purposes, then the mortgage issued the borrower would be described as “non-conforming.” If the borrower has not yet established a credit history generated in Canada, that borrower will generally only qualify for “non-conforming” mortgage financing, i.e., the Alt A mortgage market.

Conforming mortgages have the benefit of mortgage insurance, but most non-conforming mortgages do not qualify for insurance.

What is the Alt A mortgage market?

Historically, there was a divide in the residential mortgage market. The mortgage was either “A” or it wasn’t. To be an “A” residential mortgage, the borrower had to meet a very rigid criteria set by the Schedule A banks which at minimum required a three-year employment history with the same employer, income verification, three years of clear Income Tax Notices of Assessments, and a credit score 700+.

The principal reason for the rigidity was to ensure the residential mortgage would qualify for mortgage insurance. The borrower had to fit within the “box.” Any borrower that did not fit within the box would have to seek out “alternative” mortgage financing. As time passed, folks who did not fit within the box, yet had good credit, came to make up what we call today the alternative or “Alt A” mortgage market.

The risk in the residential non-conforming mortgage market is tradeable with the risk in the conforming market. The real difference between the two is that borrowers in the non-conforming market come with stories — they are “storied mortgages.”

Who invests in the Alt A mortgage market?

The Alt A market, which caters to non-conforming mortgages, has proven to be an appealing mortgage investment opportunity for a variety of people, including:

- Contractors, entrepreneurs, and small business owners who have volatile income and have a difficult time retaining traditional bank financing

- Borrowers with challenging credit history

- Asset accumulators who invest heavily in rental properties and have ‘too much debt’ on paper, making them riskier to schedule A banks

- Investors purchasing income properties or second properties for family/recreational use

- Those acquiring certain rural and agricultural properties that have residential components

- “New to Canada” immigrants who are likely to find jobs, form households, and buy homes, but do not have credit history in Canada yet

The Modern Day Playbook For Super Successful Investing

How can a smart, modern investor get in on the real estate investing action, especially since going on your own may require prohibitive amounts of capital? Most people do not have the requisite knowledge or expertise to invest in real estate on their own.

Who borrows in the Alt A mortgage market?

The people most likely to use Alt A mortgages are what we call “New to Canada.” They’re immigrants who are sought after under Federal and Provincial immigration programs designed specifically to attract those persons who possess a specific skill or trade. They are the immigrants most likely to find jobs, form households and, ultimately, buy homes. But they do not have credit history in Canada, thus the name “New to Canada.”

Other borrowers in the the non-conforming residential first mortgage market are generally persons with a challenging credit history, investors purchasing income properties, and persons purchasing second properties for family or recreational properties. The acquisition of certain rural and agricultural properties that have residential components also fit in this category.

What are the risks of investing in the Alt A mortgage market?

Most non-conforming mortgages in the Alt A mortgage market do not qualify for insurance. Therefore, pools of nonconforming mortgages cannot be collaterialized for the purposes of issuing MBSs. Because non-conforming mortgages are typically riskier and more difficult to handle, the lender will charge the borrower more. Further, as the non-conforming mortgage does not have to comply with any restrictive guidelines, the lender may allow a higher loan-to-value than if it was a conforming mortgage. The lender may also entertain borrowers with less than ideal credit history and loosen any income verification practices it employs, especially with respect to borrowers that may be self-employed or have alternative sources of income rather than traditional employment income.

Yet, apart from these differences, the underlying real property security for non-conforming mortgages may be at least the same as for conforming mortgages in that they may be located in desirable marketable areas and well maintained at the date of underwriting. Non-conforming mortgages may also carry many of the same characteristics as conforming mortgages in that the security may be the same; they may have the same payment frequency; and the loans may be amortized resulting in a recapture of capital for the lender throughout the mortgage term.

Changes in the regulatory environment have resulted in a much stronger borrower entering the private mortgage market.

Changes in Alt A mortgage regulation through the years

15 years ago, a borrower’s mortgage could qualify for mortgage insurance at a 95% Loan-to-Value (“LTV”) and an amortization period of 40 years. Employment income used to qualify for a Mortgage did not always have to be fully confirmed and/or documented and credit scores could be as low as 580. That’s no longer the case.

Regulation has evolved. LTVs are lowered and amortization periods have been shortened. In July of 2020, CMHC increased the credit score requirements of borrowers with less than 20% down payment from 600 to 680. That knocked out a huge fraction of the borrowing populace. With a sub 680 score and no insurance, that band of borrowers will have extraordinarily difficult time retaining traditional bank financing. Now, that group looks to the alternative mortgage market.

Private lending can be quite lucrative for both lenders and their investors. And in the Alt A or “non-conforming” residential first mortgage market, it can be reasonably safe as well.

The future of the Alt A mortgage market

As the rules have become much more stringent (and the types of properties insurers are willing to cover have narrowed), borrowers are looking for alternatives. Alternative lenders are desperately trying to fill this void created by regulation. Today, they can offer their investors secure long term returns of 6% to 8% (and sometimes more) simply because there are so few options for persons forced out of the traditional mortgage markets by regulation.

Canada enjoys one of the strongest real estate markets in the world. Whether the borrower is “new to Canada” or is simply the square peg that doesn’t fit Big Bank’s round hole, the Alt A mortgage market has proven to be an appealing mortgage investment opportunity for adventuresome investors who like good stories.

Start Investing in Real Estate Backed Investments Today

Explore the investments available on Fundscraper.

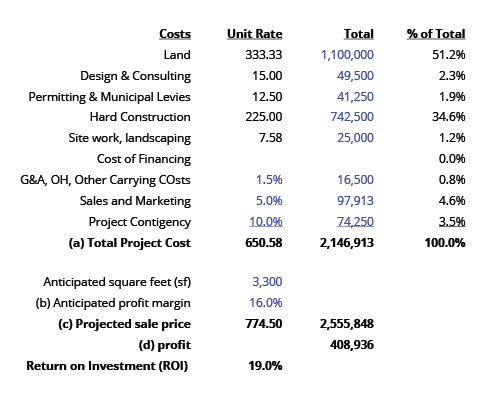

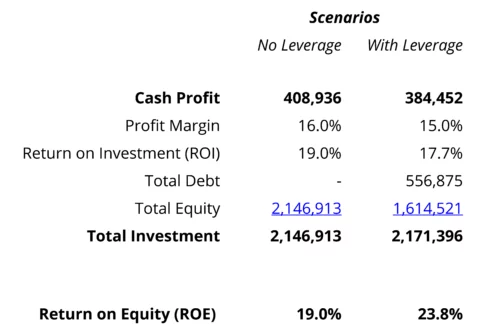

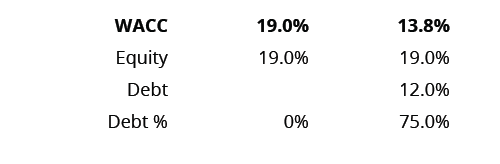

In the above No Leverage scenario, the developer maximizes the cash profit. However, they have to inject 2.146M of their own equity. For every dollar the developer invests, i.e. their equity injection, they will earn a 19% return or 19 cents for every dollar of equity. When a party invests for an ownership interest, then they have an equitable interest, or equity, and have a beneficial interest in the profits from the project. Put another way, an equity investor will likely expect or require a 19% return on their invested equity capital (the “expected return” or equity’s “cost of capital”).

In the above No Leverage scenario, the developer maximizes the cash profit. However, they have to inject 2.146M of their own equity. For every dollar the developer invests, i.e. their equity injection, they will earn a 19% return or 19 cents for every dollar of equity. When a party invests for an ownership interest, then they have an equitable interest, or equity, and have a beneficial interest in the profits from the project. Put another way, an equity investor will likely expect or require a 19% return on their invested equity capital (the “expected return” or equity’s “cost of capital”).

Your debt holders only demand 12%, but equity partners will want their 19% return. From a project point of view, the cost of that capital is going to be 19%! It’s the expected return your equity holders expect to receive by investing in the project. If you took on debt even at 12%, the math would work out to be 13.8%. So, overall, you can pay $0.138, or pay $0.19 for every dollar invested.

Your debt holders only demand 12%, but equity partners will want their 19% return. From a project point of view, the cost of that capital is going to be 19%! It’s the expected return your equity holders expect to receive by investing in the project. If you took on debt even at 12%, the math would work out to be 13.8%. So, overall, you can pay $0.138, or pay $0.19 for every dollar invested.